Biosafety

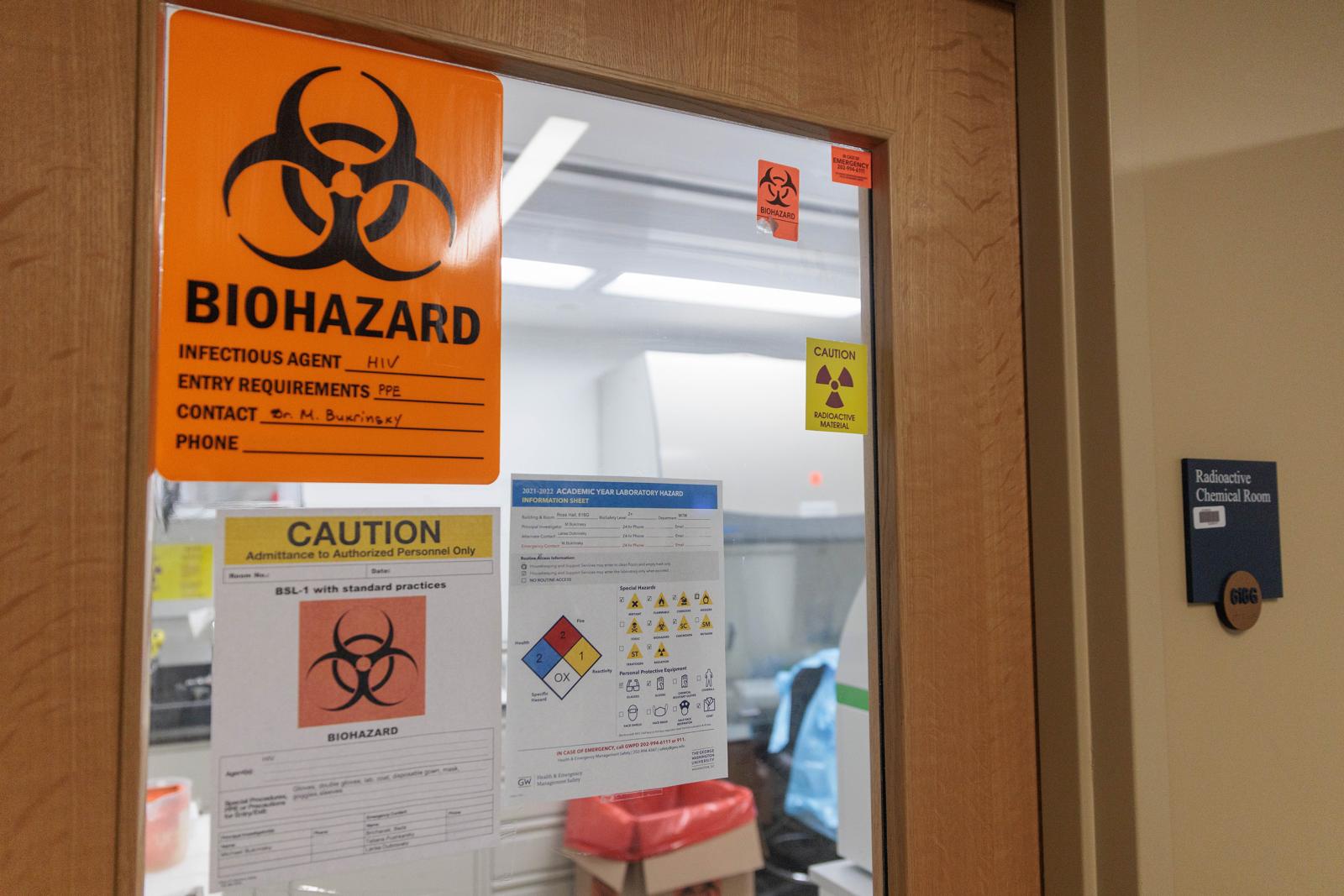

The GW Biosafety Program assist in protecting faculty, staff, students, the community and the environment by addressing the safe handling and containment of infectious microorganisms and hazardous biological materials. The practice of safe handling of pathogens and their toxins in the laboratory is accomplished through the application of containment principles and the risk assessment.

Containment Principles

Containment principles applied in accordance with the risk assessment prevent exposure of laboratory workers to a pathogen or the inadvertent escape of a pathogen from the laboratory.

Primary containment provides immediate protection to workers in the laboratory from exposure to chemical and biological hazards. Primary barriers include biological safety cabinets, fume hoods and other engineering devices used while working in the laboratory. Secondary containment is intended to protect the laboratory worker, the community and the environment from unintended contamination with biohazard materials. Secondary containment consists of architectural and mechanical design elements of a facility that prevent worker contamination and escape of pathogens from the laboratory into the environment. Personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves, laboratory coats and safety glasses may also be considered a primary containment, however, articles worn on the body are considered a last line of defense and are only used in conjunction with other primary and secondary containment elements when working with biohazardous materials.

Containment is defined in levels that increase in complexity as the risk associated with the work in the microbiological laboratory increases. All containment levels have defined primary and secondary containment features. These levels are described by a series of working practices, applied technologies and facility design built upon from a common foundation, referred to as biosafety level -1 or BSL-1. In the U. S. there are four containment or biosafety levels, BSL-1 - BSL-4. The CDC and NIH describe the criteria for each level in the Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories 6th Edition manual.

One important biosafety element suggested for all 4 biosafety levels is biosafety training. Our office provides training in biosafety to faculty, staff, students and visitors as well as the Bloodborne Pathogens training required by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) for work that has the potential to expose laboratory employees to human blood or human blood products and for procedures that require the use of a respirator.

Risk Assessment

The biological risk assessment for a microbiological or biomedical laboratory is determined by assessing the hazards posed by the biological agent and the risks of associated laboratory activities. Pathogen hazards are categorized into four Risk Groups (RG) of ascending risk (RG1-RG4). The risk group of a biological agent is determined using three criteria: Pathogenicity, or the ability to cause disease in humans or animals; Availability of medical treatment for the associated infection; and, Ability of the disease to spread. Pathogenicity is most often associated with the number of organisms required for infection (assessed in colony forming units or CFU) with bacteria that require a low number of CFU for infection considered to be more pathogenic. Medical treatment includes vaccines and antibiotics or anti-viral medications that are effective preventative or treatments for disease. The ability of an infectious disease to spread is determined by the route of infection with pathogens transmitted by aerosols considered more hazardous than other types of transmission due to the potential for multiple exposures to occur in a single incident.

The risk assessment also considers all aspects of the laboratory space that can increase the risk of exposure to a pathogen. Laboratory activities and facility design faults that are known to have caused Laboratory Acquired Infections (LAIs) are included in the overall risk assessment as well as elements of the safety program, such as training or containment features that reduce the associated risk. Because the assessment of risk is particular to the organism, the laboratory research program and design features, the risk assessment must be made for each laboratory and risk must be re-assessed when protocol or personnel changes are made.

In the Risk Assessment, risks are commonly categorized according to likelihood and consequence and are visualized in a continuum from low likelihood/low consequence - high likelihood/ high consequence- risks. As it is impossible to eliminate all risks, this type of analysis allows stakeholders to determine the level of risk that is acceptable and to focus risk mitigation efforts to higher-risk activities.

General Principles of Biological Safety Risk Assessment

General Principles of Biological Safety Risk Assessment According to the CDC’s Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories, 6th edition, the following factors must be considered when conducting a risk assessment to determine appropriate biocontainment practices:

The pathogenicity (ability to cause disease) of the infectious or potentially infectious agent. As a part of this, infectious dose, severity of the disease, history of laboratory-acquired infections and incidence in the community must be evaluated. In terms of risk, a lower infectious dose, greater disease severity, past history of lab-acquired infections, etc. are all associated with a higher risk level

The availability of effective prophylaxis and/or treatment. Identify and outline available pre-exposure prophylaxis (i.e., effective vaccines) and post-exposure prophylaxis, including passive immunizations and treatment options. Although greater disease severity often correlates with a higher biosafety level, the assignment of the biosafety level must also be determined within the context of therapeutic intervention, available vaccines, susceptibility to antibiotics or antiviral agents, etc. (Knudsen 2001)

The immune status of the employee. The outcome of infection is ultimately determined by interaction with the host, with immune status directly connected to susceptibility. Opportunistic pathogens and agents that are a part of normal microbial flora which are of no or low concern to healthy adults can cause disease in immunocompromised individuals (Fleming 2000). Therefore, underlying conditions and the risk to pregnant women (and their unborn baby) should be identified

The route of transmission of the infectious or suspected infectious agent. Unless noted otherwise, it should be assumed that agents have multiple routes of transmission (Knudsen 2001). Parenteral (injection), oral (ingestion) and airborne (inhalation) routes must be considered, and for every agent, the potential for aerosol transmission must be evaluated. Aerosols are considered the most dangerous route of transmission because of the large number of personnel that can be infected and because most laboratory-acquired infections are known (or suspected) to be contracted via aerosol exposure (Knudsen 2001). The route of transmission in the community should also be noted

The agent’s viability in the environment. Identify factors (desiccation, exposure to sun or UV light, susceptibility to heat or chemical disinfectants, etc.) that affect the infectious agent’s stability in the environment. There is a greater risk associated with organisms that can persist in the environment. Agent stability is also related to aerosol infectivity, in that inactivation of viable aerosols limits transmission via this route

The origin of the potentially infectious agent. Evaluation of the origin should include host (e.g., symptomatic or asymptomatic animal), geographical location (e.g., domestic or foreign), association with zoonotic infection or disease outbreak and ability to endanger livestock. The host range of the agent should also be determined

The planned activities. The activities should be evaluated for, among other things, their propensity to generate aerosols and how much handling of the sample materials is required. Examples of activities include sonication, centrifugation, those requiring or resulting in agent amplification and those involving sharps

- The experience/skill level of at-risk personnel. At-risk personnel directly handling the infectious or potentially infectious materials should be identified and their experience and skill level evaluated. Depending on the operation, at-risk personnel might also include maintenance workers, custodial staff, etc. If additional training is necessary to ensure safety, it should be considered.

The compilation of this information will be used in order to assign the biosafety level for a procedure and to identify corresponding work practices, engineering controls (i.e., containment devices) and personal protective equipment.

Additional Resources on Risk Assessments:

- CDC Guidelines for Biological Risk Assessment Process

- BSL-2 with BSL-3 practices summary based on CDC/NIH “Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories”

- Assessing Biological Risks

- Risk Assessment Principles

- Developing a Biosafety Risk Assessment for Biological Select Agents and Toxins (BSAT)